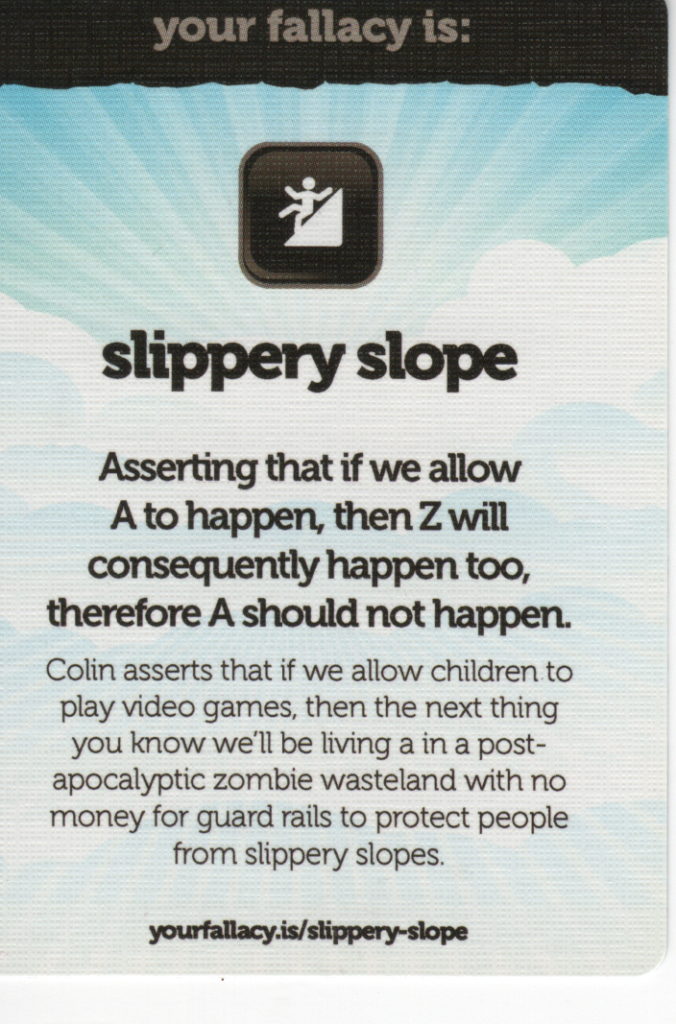

As I go through each of the fallacies I’ve been writing about, I have to try to remember that they are only fallacious in the sense of an idealized debate. That’s one in which the debate is conducted strictly by the rules of logic (and of course, which assumes the underlying truth of the premises each side uses when debating). So, the slippery slope “fallacy” is definitely one if you and I are arguing having agreed to abide by the rules of logic. Actual arguments out there in the world don’t work that way, of course; they rely at least as much on appeals to emotion as they do reason. The slippery slope argument definitely has that appeal, just as all of the other fallacies do.

I’ve been wondering this, though: how do you know when someone is using the slippery slope to simply score points in a debate, and how do you know when the slippery slope is real?

For example: am I using a slippery slope argument if I were to argue that the last decade or so in America has seen a rise in right-wing rhetoric which has led to increased (threats of, as well as actual) violence towards groups historically marginalized here? A person accusing me of doing that (e.g., “Well, words can’t hurt people, so just because I can say racist/sexist/etc. things doesn’t mean that I’m going to become violent towards those people; you’re using a slippery slope argument!”) would be correct in requiring that I show causation. That is, I am required to prove (in some rigorous sense) that the claim that rising right-wing rhetoric has directly led to increased violence, and that I am not just making a slippery slope argument.

I think this is where I’d have to try to fall back on a genuinely American invention: abductive reasoning. Charles Peirce, back in the 19th century, argued that it was reasonable to draw the simplest conclusions from observations, while recognizing that there was still some uncertainty in those conclusions. So, by abductive reasoning, I might argue that:

- There has always been right-wing rhetoric and violence against marginalized groups.

- That rhetoric has risen in frequency and intensity in the last decade.

- It is also the case that there has been increased violence against marginalized groups over that time period by right-wing actors.

- Therefore, it seems plausible that the intensification of rhetoric has led to increased violence.

I suppose, looking at it this way, one could abductively argue the converse; it is plausible that the increase in violence has led to the intensification of rhetoric. I could argue (non-abductively) that the conclusion I originally wrote is MORE likely than the converse, but I couldn’t prove it.

Which brings us back to the “slippery slope”. In a one-off debate, a slippery slope fallacy can be identified fairly easily, but what happens in a world where the mechanisms of communication tend to not just allow, but actively incentivize, more and more heated rhetoric? Is it really a slippery slope argument to say that I fully expect more violence to occur down the road because Twitter has reinstated many banned right-wing accounts, for instance?

I guess we will see.